The Vietnam War was awful, and America was part of it…

The Vietnam War wasn’t just another overseas conflict—it was a bloody, complicated, and divisive chapter that scarred an entire generation of Americans. More than 58,000 American soldiers died, countless Vietnamese civilians were killed, and the country back home was torn in two over why the U.S. even got involved in the first place.

So why did America dive headfirst into a war halfway across the world, in a country most Americans couldn’t even find on a map at the time? It wasn’t one single reason. It was a mix of fear, ideology, miscalculations, and pride. Let’s break it down in the following lines.

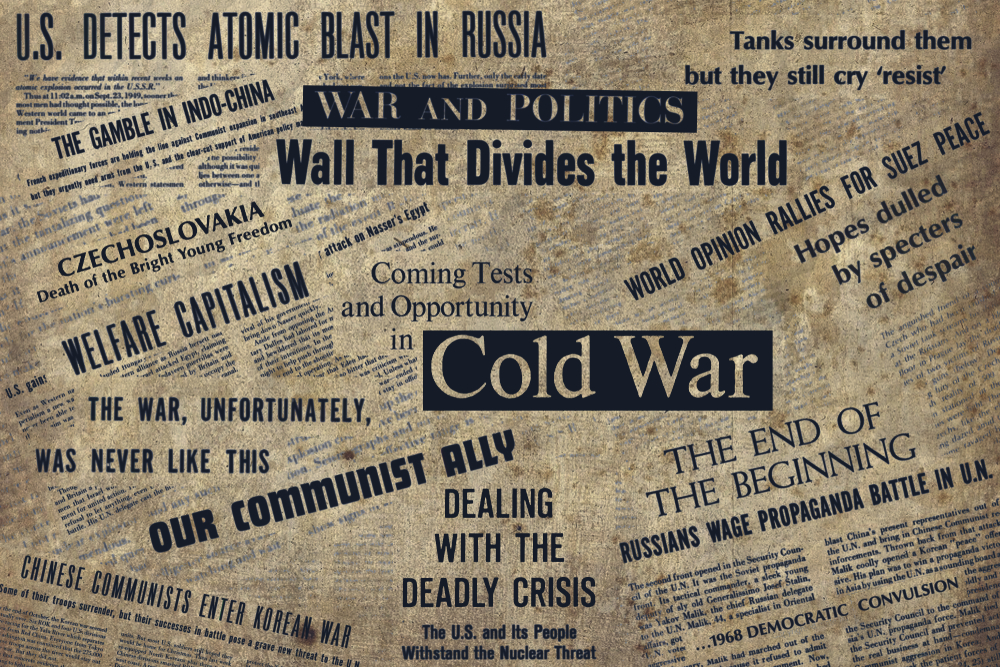

The Cold War and fear of Communism

If you want to understand Vietnam, start with one word: communism. The U.S. didn’t go to Vietnam just because it had beef with the North Vietnamese. It went because it was terrified of the spread of communism.

After World War II, the world was split into two ideological camps: capitalism, led by the U.S., and communism, led by the Soviet Union. This era, known as the Cold War, wasn’t fought through direct battles between the superpowers but through proxy wars, and Vietnam became one of the biggest ones.

The idea was simple: If one country “fell” to communism, its neighbors would follow. This became known as the Domino Theory. If Vietnam turned red, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and even parts of Indonesia might fall too. The U.S. couldn’t let that happen—or so it believed.

The legacy of French colonialism

Before the U.S. ever stepped into Vietnam, the French were already knee-deep in the mess. Vietnam had been a French colony since the 1800s. But after World War II, nationalist and communist forces under Ho Chi Minh fought for independence.

In 1954, the French suffered a humiliating defeat at Dien Bien Phu, and Vietnam was temporarily divided at the 17th parallel—North Vietnam under Ho Chi Minh (communist), and South Vietnam under Ngo Dinh Diem (anti-communist, U.S.-backed).

The U.S. didn’t want Vietnam to become another China, where communists had taken control in 1949. S,o instead of letting the region work out its future, America stepped in to fill the gap France had left behind.

It happened like a Domino game

The Domino Theory wasn’t just some political buzzword—it was the main reason the U.S. got involved. President Dwight D. Eisenhower pushed it hard in the 1950s, warning that if South Vietnam fell, the entire region would follow. This fear continued through the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

Whether or not the theory was actually valid didn’t matter—perception ruled policy. America saw Vietnam as a line in the sand. If they didn’t stop communism there, it would spread uncontrollably.

Support for South Vietnam

In the early years, the U.S. involvement was mostly indirect—sending advisors, money, and equipment to support South Vietnam’s government. But that government, led by Ngo Dinh Diem, was corrupt, authoritarian, and unpopular with its own people.

Still, the U.S. backed him anyway. He was anti-communist, and that was good enough. Even after Diem was overthrown and assassinated in 1963 (with U.S. approval, no less), America doubled down. Why? Because by then, the U.S. had sunk too many resources into the region. Pulling out would’ve looked like admitting defeat.

The Tonkin incident

In August 1964, the USS Maddox, a U.S. Navy destroyer, was reportedly attacked by North Vietnamese forces in the Gulf of Tonkin. Whether the second attack actually happened is still debated, but President Lyndon B. Johnson used the event to push for more military action.

Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, giving Johnson broad powers to escalate U.S. involvement without an official declaration of war. This was the moment the Vietnam War shifted from support and advisors to full-blown combat.

…The President had pride, but the political pressure was also huge

Once Johnson had the authority, he didn’t hold back. He increased troop levels dramatically. By 1968, there were over 500,000 U.S. troops in Vietnam. Why? Because backing down wasn’t an option. It would’ve been political suicide.

Presidents—both Johnson and later Nixon—didn’t want to be the one who “lost Vietnam.” There was enormous pressure from military advisors and politicians to maintain U.S. credibility. If America retreated, it would send a signal to the world that the U.S. didn’t have the guts to stand up to communism.

So even as things got bloodier and more hopeless, they kept pushing forward.

Americans were unaware of the people and politics

Another big reason for U.S. involvement? Complete misunderstanding of Vietnam’s people and politics. Washington painted the North Vietnamese as puppets of Moscow or Beijing. But Ho Chi Minh was a Vietnamese nationalist first, and a communist second. He wanted independence more than a global communist revolution. But to the U.S., communism was communism, and that meant it had to be stopped.

This misunderstanding led to flawed strategy and disastrous decisions, like relying heavily on bombing campaigns and assuming the Vietnamese would fold under military pressure.

Wanna read more about the Vietnam War? This book is a great source of info!

Military-Industrial Momentum

Let’s be blunt: war is big business. By the 1960s, America had a powerful military-industrial complex—a term coined by President Eisenhower himself. Defense contractors, generals, and politicians all had a stake in continuing the war.

Every escalation meant more weapons, more contracts, more careers being made. The gears of war don’t stop easily once they’re in motion. This isn’t to say the war was fought only for profit, but once it started, there were powerful interests who had every reason to keep it going.

Fear of looking weak

International politics is a game of image. America had built itself up as the defender of freedom. Losing in Vietnam would shatter that image, especially after backing South Vietnam for so many years.

Johnson and Nixon both feared what would happen if they “cut and ran.” The Soviets would feel emboldened. Allies would doubt U.S. protection. And domestic critics would have a field day. So, pride became policy. And thousands of young men paid the price for it.

The Vietnamese people are now facing dire circumstances

Once you’re waist-deep in a swamp, it’s hard to turn back. That’s what Vietnam became—a quagmire. Each year, the U.S. sent more troops, dropped more bombs, and spent more money. And every year, the situation got worse.

But rather than admit the strategy was broken, leaders kept doubling down. No one wanted to be blamed for losing. It was a war driven by inertia and the hope that one more push would turn the tide. It never did.

Bottom line:

The Vietnam War wasn’t caused by one decision, one president, or one ideology. It was a slow-motion disaster built on Cold War paranoia, bad intelligence, political pride, and an obsession with global image.

The U.S. got involved in Vietnam to stop communism. But it underestimated the enemy, misunderstood the region, and overestimated its own ability to force change. The result? A brutal war that cost over 58,000 American lives, destroyed trust in the government, and left deep scars that still haven’t fully healed.

And maybe, just maybe, it taught a lesson about the true cost of fear-driven foreign policy.

Check out 7 Forgotten Towns in American History: Where Did They Go?